What Might Happen To Public Pensions In The Wake Of Covid-19?

Part 1

May 11, 2020

GFRC Associate Director Amanda Kass has deep expertise in the world of pensions. This knowledge base provided her with the background to research and write the following, longer-than-usual blog item for GFRC about the nexus of public pensions and the coronavirus. Following is the fruit of her labors:

We are currently in the midst of unprecedented economic upheaval tied to the COVID-19 pandemic and necessary policies to mitigate its spread. The US economy came to an abrupt stop as businesses closed and people sheltered-in-place. This sudden halt to everyday life and related economic disruptions are most vividly demonstrated by the record number of people filing for unemployment benefits (30 million as of the end of April).

The economy’s sudden, dramatic downturn has important implications for government finances, with immediate effects felt in increased costs and declines in tax collections. In other words, governments are faced with the pressure of needing to spend more at a time when they’re taking in less revenue. Another area that may be hard hit are public pension systems, which rely heavily on investment returns as a source of funding. Pension systems suffered significant investment losses during the 2007-2009 recession, which decreased their overall funding levels.

Given the economic downturn and uncertainty tied to COVID-19, what might happen to public pensions? Headlines warn that COVID-19 may worsen the “public pension crisis”, and more recently, the Illinois Senate President made the national news for asking Congress to “bail out pensions.” While underfunded pension systems are often discussed as a singular issue, the financial condition of a public pension system is a concern for two separate (but interrelated) reasons: 1) increased government contributions, which would compound the fiscal stress of decreased revenue and increased spending; and 2) the pension funds completely running out of assets, which could mean a halt to benefits being distributed.

My aim with this blog is to highlight how the economic downturn might impact public pension systems and government finances.

What Happened During the Last Recession?

While there is great uncertainty as to how long this economic downturn will last and what recovery will look like we can look at what happened to public pension systems in the wake of the 2007-2009 recession to get a sense of the (potential) magnitude. In the wake of that recession, the funded ratio for state and local plans nationwide decreased from 86% in 2007 to 72% in 2017. This national level data, however, masks important differences. Boston College’s Center for Retirement Research divided state and local pension systems into three groups based on their 2017 funded status and found there is growing divergence between well and underfunded pension systems. Today, the average funded ratio for the group of well-funded systems is 90% funded, while it’s only 55% funded for the least funded group. Moreover, the least funded systems’ average funded ratio declined by nearly 17 percentage points between 2007 and 2017, a much larger decline than experienced by the better funded systems.

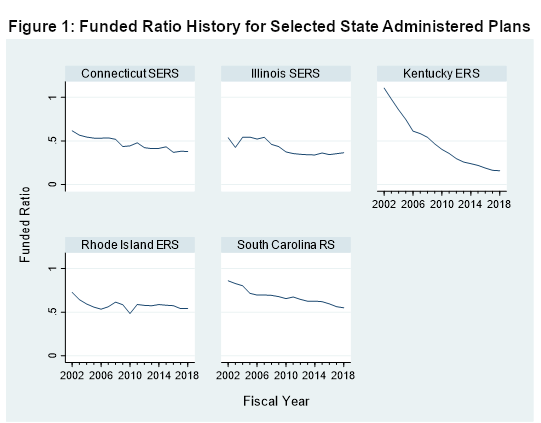

A key issue is that many state and local pension systems are much less funded than they were prior to the 2007-2009 recession, as highlighted by Figure 1. Figure 1 shows the funded ratio histories for the five state administered pension systems for public employees that had the lowest funded ratios as of the end of FY2018.1

Part 2

The economic downturn tied to COVID-19 may be more severe than the last recession, in which case pension systems’ finances could decline even more dramatically than they did during that event. Such a scenario is especially worrisome for state and local governments (like Illinois, Kentucky and South Carolina) that have seen the finances of their systems decline over time and already had significantly underfunded systems. Further drops in their funding levels risk the systems becoming insolvent and/or dramatically increasing governments’ required contributions.

Pensions heavily rely on investment returns as a funding source, and the other two funding sources are employee and government contributions. Governments’ contributions are tied to the pension systems’ funding levels and achieving a funding goal. The funding goal for Illinois’ state systems is being 90% funded by the end of FY2045, and each year actuaries determine how much the state needs to pay to meet that goal. As a pension system’s finances decrease, required government contributions increase.2 There is a bit of a lag to this dynamic, so increased pension contributions from the COVID-19 economic downturn may not materialize as quickly as revenue shortfalls. In a recent IGPA report, my colleagues and I highlighted how in the wake of the last recession Illinois’ actual pension contributions for years 2009 through 2018 were much higher than anticipated.

Regardless of the exact timing, unexpected and large increases in required pension contributions would exacerbate the fiscal pressure governments will already face due to revenue shortfalls and increased expenses. This is exactly what happened after the 2007-2009 recession.

What Might Be Different This Time?

Pension systems experienced a drop in assets during the last recession, and many underfunded pension systems (like those in Illinois and Kentucky) are less funded than they were prior to that economic downturn. At the extreme, there are some public pension systems that are so poorly funded they risk running out of assets due to investment losses, governments inability to make pension payments, or a combination of the two.

At this juncture it’s hard to know the magnitude of how government finances and public pension systems will be impacted, in large part because it’s unclear what economic recovery will look like or when it will begin. How big of a loss in assets pension systems will experience will vary from fund-to-fund and will depend on their asset allocation. Theoretically the pandemic could be abetted, economic activity could resume, and investment losses today could be largely offset by future gains, meaning there’s a minimal net impact. Long-story short though, the greater the pension systems’ investment losses are, the higher future pension contributions will be (absent other changes, like benefit cuts). Even if pension systems don’t suffer large investment losses, it may be difficult for governments to make their required pension payments as they grapple with higher than expected expenses and revenue losses tied to COVID-19

There is also a danger that some of the least funded pension systems may deplete their assets and be unable to pay benefits to retirees. In the last recession, while many public pension systems’ funded ratios dropped significantly there was one place (Prichard, Alabama) where a fund ran out of money and benefits were actually halted. The City of Prichard had long faced fiscal problems, and it had filed for bankruptcy previously in 1999. It filed again in 2009 amidst a lawsuit from retirees over the halted benefit payments. A settlement was ultimately reached in Prichard in which retirees would get just one-third of their promised benefit.

While Illinois’ state pension systems are 40% funded there are dozens of municipal pension systems within the state that are even less funded. The City of Chicago’s four pension systems were just 25% funded at the end of FY2018. The funded ratios of police and fire pension funds in 20 municipalities were less than 30% funded as of FY2016. Many of those places have limited fiscal capacity–the majority have high poverty (averaging 20%), and nearly half saw their population decline between 2000 and 2010. These municipalities were already struggling to make the required pension payments, and the COVID-19 economic downturn will magnify that fiscal stress.

It’s possible that extreme pension difficulties could push a municipality to bankruptcy, particularly if accompanied by a variety of other fiscal problems. But historically public sector bankruptcies have been rare. Between 1980 and 2016 there have been 297 bankruptcy filings, the majority of which have been by special districts and utilities. In the wake of the 2007-2009 recession, Meredith Whitney infamously predicted there would be a wave of cities defaulting on their debts. But only eight municipalities filed for bankruptcy in the wake of the 2007-2009 recession (the largest city to do so was Detroit). And while Senate Leader Mitch McConnell opined that states should go bankrupt rather than having the federal government bail them and their underfunded pension systems out, state governments, which are sovereign entities, cannot file for bankruptcy for legal and constitutional reasons. Municipal governments can file for federal bankruptcy, but only if state laws provide authority to do so.3

More likely, if a pension system depleted its assets it could revert to being pay-as-you-go (PAYGO), at least in theory. As currently designed, pensions are meant to be pre-funded–meaning that during the course of an individual’s employment, through a combination of employee contributions, employer contributions, and investment returns enough money accumulates to pay for their benefits once they retire. With PAYGO, money is not set aside and benefits are paid as they come due.

One issue with switching from pre-funded to PAYGO is that PAYGO could require payments that exceed governments’ current payments. For example, in 2018, Chicago’s payment to its municipal employees’ pension fund was approximately $350 million while benefit payments (including refunds) exceeded $900 million. Of note, Chicago’s payment in 2018 was a fixed amount set by state statute, and is well below the Actuarially Determined Contribution (ADC). The ADC is a metric created by the Governmental Accounting Standards Board that is used to evaluate whether employers are sufficiently funding employees’ benefits, based on achieving full funding in a specified time period (another approach is called net amortization). What state and local governments actually have to pay is determined by state and local laws, and Illinois’ funding laws differ from the ADC. If Chicago was required to pay the ADC, its contribution in 2018 would have been $1.05 billion, greater than the benefit payments made that year.

Another concern is that if a pension fund runs out of money, governments may choose not to make the benefit payments (as happened in Prichard) and argue that they are not legally responsible to make benefit payments. This is the logic the Rahm Emanuel administration used several years ago to justify changes it sought to make to two of Chicago’s pension systems (the laborers’ and municipal employees’ funds, referred to as LABF and MEABF). Until recently, Chicago’s contributions to the LABF and MEABF were not tied to a funding plan, and as a result the funds were projected to run out of assets. To avoid that scenario, then Mayor Rahm Emanuel advocated for cutting benefits while also putting in place a funding plan that would require increased city contributions.

His plan became law (Public Act 98-641), but was contested because the Illinois Constitution contains a provision protecting public pension benefits. In court, the City of Chicago argued that the totality of the changes were a net benefit to members of the pension systems because without changes to the funding laws the systems would go insolvent. And, importantly, “The City additionally maintained that any payment of benefits owed prior to the Act was not the obligation of any government entity but, rather, was the obligation solely of the Funds themselves and that under the Pension Code ‘participants’ benefits [were] limited to sums on hand in the funds.” In other words, the City’s position was that it was not on the hook to pay benefits should the LABF and/or MEABF run out of assets. The Illinois Supreme Court ruled against the City in that case, and a new funding plan, without benefits cuts, was created.

It is unclear whether any pension funds in Illinois, or across the country, will run out of assets. What exactly would happen if a pension fund runs out of assets is also unclear, and state laws and constitutional provisions vary significantly in terms of pension protections, as well as state laws concerning the wider issue of municipal insolvency. Many of the places in Illinois with the most severely underfunded pension systems are already grappling with fiscal challenges tied to long-term trends of population decline, manufacturing and industry loss, and increased poverty. Prichard, Alabama is an example of a worst-case scenario of a community forced to choose between funding current services and sending retirees their monthly benefits. After halting benefit payments for several years, the City of Prichard eventually reached an agreement in which retirees would receive a benefit that was one-third of their original pension. The agreement didn’t cover current employees though, and the City’s financial troubles have continued.

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————

Footers

Endnotes

1 Many states have multiple public pension systems, and the data in Figure 1 is for specific pension systems. For example, Illinois has five pension systems, and Figure 1 shows the funded ratio history for only the State Employees’ Retirement System.

2 In addition to the investment performance, funding levels are affected by how closely actuarial assumptions (for things like investment performance and mortality) align with reality. Changes to assumptions also impact funding levels, and in-turn impact government contributions.

3 Municipal governments in Illinois generally do not have that authorization; however, communities with a population of 25,000 or less can obtain permission to file for Chapter 9 in limited circumstances (two villages did file for bankruptcy in the 2000s without such authorization).