Hydrogen Fuel Cells: A Case Study on the Power of the White House to Shape Federal Funding for R&D

Introduction

By Zach Perkins, Graduate Student at the University of Illinois Chicago

February 25, 2025

Throughout its nearly fifty-year history, the Department of Energy (DOE) has undertaken research in a diverse variety of technology areas. Although many factors influence these decisions, including Congressional legislation, internal DOE priorities, and market dynamics, one of the key overarching influences over DOE program areas has been the energy policy goals of each presidential administration. One of the best examples of this is the Bush Administration’s Hydrogen Fuel Initiative (HFI), which heavily influenced research and development (R&D) efforts within the DOE’s Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy (EERE) during the early 2000s. Although the initiative made up a significant portion of total EERE funding each year of the Bush Administration, the long-term success of these efforts has been questioned as hydrogen vehicle technology has failed to become “practical and affordable” by 2020 as called for by the HFI. Despite this, the Bush Administration’s aggressive support for hydrogen fuel cell technology acts as an informative case study into the influence of White House energy policy on EERE R&D decisions.

HFI Timeline

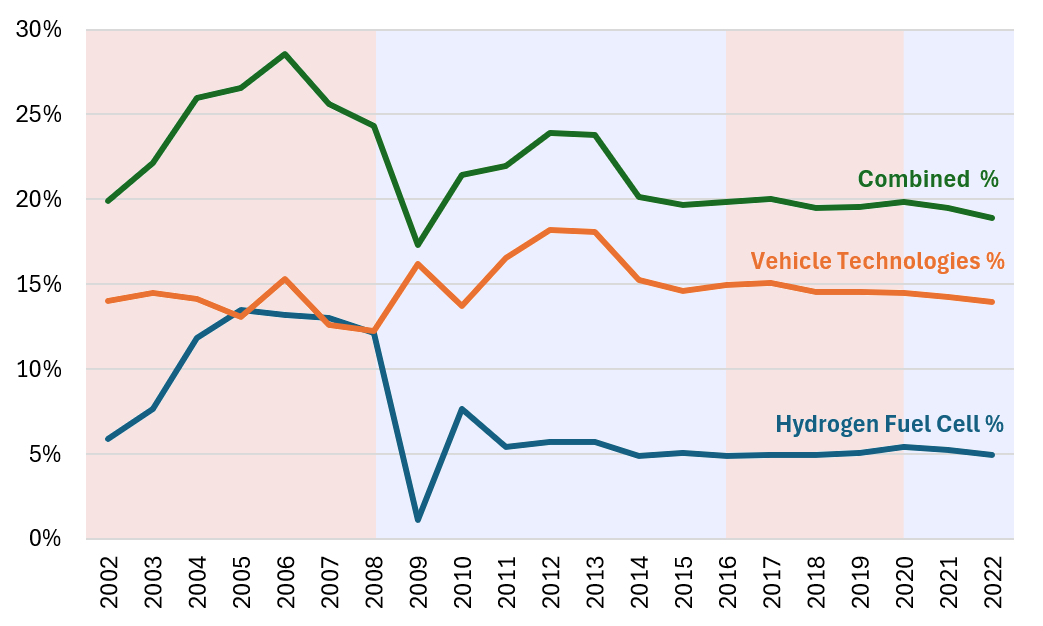

In January 2002, President Bush announced the FreedomCAR initiative, a public-private partnership with American automakers to encourage investment and collaboration in high-risk pre-competitive automotive technologies, including hydrogen fuel cells. Although fuel cell R&D faced initial criticism for its lack of immediate market-ready applications, President Bush solidified his commitment to the technology when he announced the HFI in early 2003, committing a combined $1.7 billion to both FreedomCAR and hydrogen fuel cell initiatives. Two years later, President Bush signed the Energy Policy Act of 2005, which once again codified his administration’s hydrogen fuel focus along with other renewable energy goals including zero-energy buildings, clean biodiesel, and hybrid-fuel vehicles. This act also hoped to incentivize the adoption of hydrogen fuel through the introduction of 30% tax credits on alternative fueling equipment and vehicles. These efforts strongly influenced EERE’s budget allocation, with the office’s Hydrogen Fuel Cell Technologies and FreedomCar & Vehicle Technologies programs combined exceeding 25% of EERE’s total budget share for FY 2004-2007, a number it would fail to surpass again in the future (See Figure 1).

Despite significant White House support for fuel cell R&D, by the end of the Bush Administration, it had become increasingly clear that these efforts would fall short of their initial goals, with hydrogen-powered vehicles remaining costly and inefficient, especially when compared with the many promising breakthroughs in electric and hybrid-vehicle technologies. In his 2006 State of the Union speech, President Bush publicly expressed the need to increase support for battery-powered and clean-diesel vehicles, foreshadowing EERE’s pivot towards electric vehicle R&D. Political will for prioritizing hydrogen fuel cell R&D quickly took a backseat role in favor of more short-term market-ready solutions by mid-2008 as oil prices soared to a record $150 per barrel in the dawn of the Great Recession.

This shift only accelerated following President Barack Obama’s 2008 victory, leading to a recalibration of energy policy goals within the White House. In particular, the Obama Administration provided strong incentives for electric vehicles within the colossal $787 billion American Reinvestment and Recovery Act. Furthermore, President Obama’s DOE Energy Secretary appointee, Steven Chu, sought to pivot the department’s focus away from hydrogen fuel cells in favor of technologies with more immediate promise, leading the FreedomCAR program to evolve into the electric-focused US DRIVE program, which expanded to add new partners such as Tesla Motors. While EERE would continue to invest in hydrogen fuel cell R&D throughout the 2010s, it would never again reach the level of investment it recieved during the early 2000s.

Motivations

Although there were many factors involved, there were three key motivations behind the Bush Administration’s support of hydrogen fuel cell R&D during the early 2000s: Energy Security & Independence, Environmental Goals, and Auto-Industry Support. Each of these three motivations interplayed with one another, ultimately resulting in an over $1.2 billion investment in hydrogen fuel programs.

1. Energy Security & Independence

Perhaps the most prominent factors guiding energy policy during the early 2000s were concerns over energy security and independence. Although these have always played a role in EERE funding decisions, the September 11 Attacks and subsequent War on Terror sparked a renewed interest within Washington to reduce American dependence on foreign oil, whose prices steadily climbed throughout the decade. Additionally, events such as Hurricane Katrina and growing demand for oil in China and India placed further strain on American energy costs. While broad investment in clean energy was seen as a promising solution, hydrogen fuel in particular provided an encouraging strategy to appeal to energy security concerns while addressing the concerns of environmentalists and supporting auto-industry goals.

2. Environmental Goals

Although environmental motivations took a secondary role to energy security and independence, growing awareness of Climate Change was another key driver of energy policy during the early 2000s. Moving away from traditional gas-powered vehicles in favor of clean energy alternatives appeared a promising way to decrease transportation-related emissions, which continue to make up 28% of total American greenhouse gas emissions today. While hydrogen fuel presented an opportunity to decrease these emissions, the HFI was criticized by many environmentalists and fiscal conservatives alike for being a costly early-stage technology with unclear short-term viability. Additionally, much of the administration’s R&D funding went to producing hydrogen fuel cells through legacy fuel sources such as gas and coal, leading many environmentalists to believe the HFI would simply transfer emissions from one fuel source to another.

3. Auto-Industry Support

Because hydrogen fuel could be produced from fossil fuel sources, including natural gas, it was seen as a less radical way to transition to clean fuel by many auto-makers. Additionally, electric battery-powered vehicle technology at the time was still in its infancy with short battery life and long charging times, making hydrogen fuel cells an appealing alternative. As part of the FreedomCAR partnership, several industry-led pilot programs such as Ford’s Focus FCV and General Motors’ HydroGen were developed to demonstrate private-sector support and the viability of fuel-cell technologies in the American auto-market.

Conclusion

While the legacy of the HFI is often debated, the initiative presents a uniquely poignant example of White House energy policy influencing EERE R&D investments. There has also been a recent resurgence in discussions surrounding hydrogen fuel-cell applications, with the lessons of the HFI proving vital to future public and private sector R&D. It is important to note however that White House support on its own is not enough to determine EERE decision-making. For example, during the first Trump Administration, the White House sought to drastically reduce the scope of EERE programming to only include early-stage pre-competitive R&D, proposing up to 87% budget cuts each fiscal year. These cuts did not materialize indicating that a mixture of presidential and congressional support is necessary in order for White House energy initiatives to reach the level of broad support the HFI experienced.

The contents of this blog post reflect the author’s views, and not necessarily those of the GFRC.

Figure 1 –Hydrogen Fuel Cell and Vehicle Technologies as percent of total EERE budget

Figure 1 –Hydrogen Fuel Cell and Vehicle Technologies as percent of total EERE budget

Source: 2002-2022 EERE Budget Requests

About the Author

Zach Perkins is a first-year Master of Urban Planning and Policy student with a specialization in Economic Development at the University of Illinois Chicago. Zach has a dual-degree in Economics and Public Policy Analysis from The Ohio State University and has professional experience working with a neighborhood development corporation, where he focused on researching housing investment disparities and developing an active transportation plan.