The Cook County, Illinois, Sweetened Beverage Tax: A Missed Opportunity

June 14, 2021

By Lisa M. Powell, Distinguished Professor and Director, Health Policy and Administration, School of Public Health, University of Illinois, Chicago and Julien Leider, Senior Research Specialist, Institute for Health Research and Policy, University of Illinois, Chicago

Sugar-sweetened beverage (SSB) taxes have been implemented in eight local jurisdictions across the U.S. since Berkeley, California, became the first to do so in 2015. SSB taxes are designed to raise revenue while discouraging soft drink consumption, which is linked to numerous health problems.

Both of these goals have taken on additional urgency with the COVID-19 pandemic. That’s because, over the course of the pandemic, state and local finances have been challenged, chronic shortfalls in funding for public health initiatives have been highlighted, and obesity, type 2 diabetes, and cardiovascular disease -- all of which are associated with SSB consumption-- have been shown to be associated with increased risk of severe illness from COVID-19.

Cook County, Illinois, implemented a one cent per ounce tax on SSBs, as well as beverages that are artificially sweetened, on August 2, 2017, but it was repealed only four months later, effective December 1, 2017. The tax's implementation was delayed while confronting legal challenges and it was subject to intense political opposition once it was in place. Research has suggested that poorly managed messaging and campaigning for the tax as well as a broader local climate of "tax fatigue" and distrust in local government contributed to the failure of the tax.

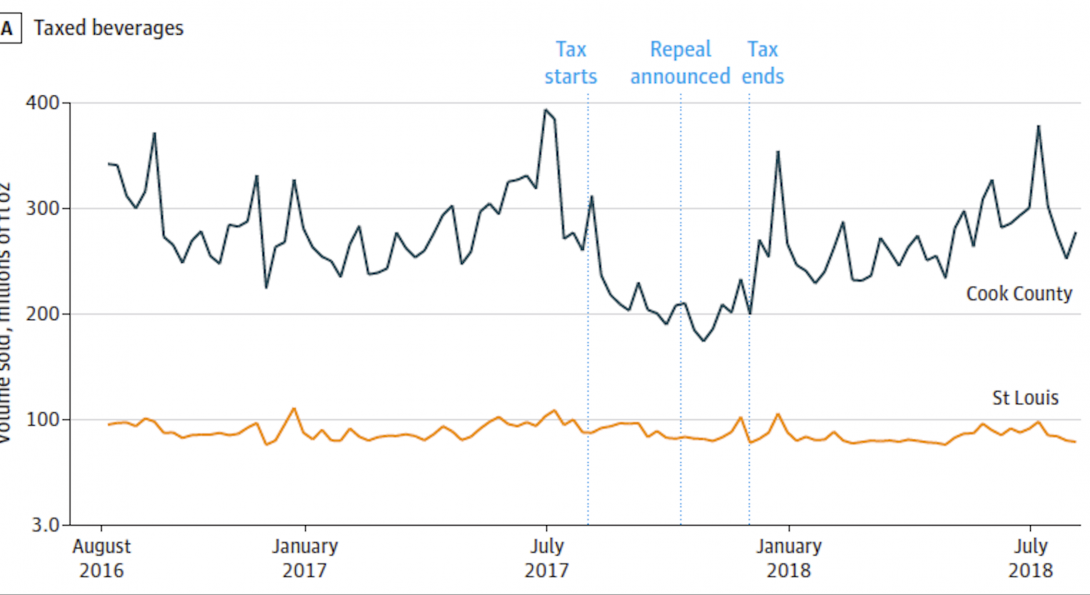

While the tax was in place, it was effective in raising some $61.6 million in additional revenue, and reducing demand for SSBs. On an annual basis, the tax could have contributed approximately 10 percent of total tax revenues for the county. Of the revenue actually raised during the short four months that the legislation was in effect, 27 percent was contributed to the county's health enterprise fund, with the rest going to the county’s general fund. At the same time, the volume of taxed beverages sold declined by 21 percent even after accounting for cross-border shopping. Following the repeal of the tax, however, volume sold returned to its pre-tax levels (see chart).

Other U.S. sweetened beverage taxes have also effectively reduced demand for sweetened beverages and raised significant amounts of tax revenue. The tax in Philadelphia (which, like Cook County's, also applied to artificially sweetened beverages), reduced demand by 22 percent to 38 percent after accounting for cross-border shopping and has been estimated to raise $3.81 per capita in monthly revenue on average (higher than the monthly revenue of $2.95 per capita raised by Cook County's tax while it was in place). The tax in Oakland, is estimated to have reduced volume sold by 8 percent after accounting for cross-border shopping, and the Seattle tax is estimated to have reduced volume sold by 22 percent with no evidence of cross-border shopping. The Oakland and Seattle taxes, which only apply to SSBs, have raised $2.00-$2.43 in monthly revenue per capita.

Sweetened beverage taxes have faced significant opposition in other jurisdictions besides Cook County, and while no other tax has been repealed, several states have passed legislation preempting further local taxes.

Concerns that have been raised in opposition to sweetened beverage taxes include cross-border shopping, tax regressivity and job losses. However, research suggests that cross-border shopping only partially offsets reductions in demand. Taxes covering broader geographic areas, such as a state-level tax, could help to limit this.

With respect to concerns related to regressivity, public health benefits from such taxes are likely to be highest for lower-income and minority individuals because their baseline SSB consumption is higher, and revenue from the taxes can be used to benefit disadvantaged populations.

Finally, peer-reviewed studies of tax impacts on employment in Philadelphia and San Francisco, and unemployment in Philadelphia have failed to find any net negative impact of sweetened beverage taxes on employment. Additionally, given associations with obesity, lower consumption of SSBs is likely to be associated with lower medical costs and improved worker productivity.

In summary, the Cook County sweetened beverage tax was successful while it was in place in both raising revenue and reducing demand for taxed beverages, mirroring the experiences of other local U.S. jurisdictions that have implemented such taxes. The repeal of the tax represents a missed opportunity to address an important public health problem, but similar measures remain a ripe area for action by other local jurisdictions or states.