Slow To Spend? State Approaches To Allocating Federal Coronavirus Relief Funds

part 1

By Amanda Kass and Isabella Romano

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has had unprecedented health, economic and fiscal consequences. State and local governments are facing significant budget gaps because of sharp revenue declines and increased spending demands. To address the crisis, Congress passed a series of stimulus bills in March 2020, the largest being the $2 trillion Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act.

While the CARES Act mainly provided relief for individuals and businesses, it also set aside money to cover state and local governments’ unexpected COVID-19 related expenses. More specifically, the CARES Act appropriated $150 billion to the Coronavirus Relief Fund (CRF) so the Treasury Department can make payments to states, territories, local governments and tribal governments for COVID related expenditures.1 While governments have discretion over how to use the money, the funds can only be used for expenses that meet the following criteria:

- Necessary expenses tied to the “public health emergency with respect to COVID-19”;

- Expenses that were not accounted for in the state or local government’s budget that was approved as of March 27, 2020; and,

- Expenses that are incurred between March 1, 2020 and December 30, 2020.

It is unclear why the deadline for spending CRF funds was set as December 30, 2020. This limit makes little sense given that the pandemic is ongoing (with second and third waves of spiking cases occurring). Moreover, as we highlight in this report, changing guidelines from the Treasury Department have led to confusion and spending delays. The December 30 date is arbitrary and Congress could change it to ensure state and local governments fully utilize the Coronavirus Relief Fund program.

How Has the Treasury Department Apportioned CRF Money?

Although the CARES ACT did not address the full fiscal needs of subnational governments, it did provide $150 billion to them for unexpected, COVID- related expenses. Of the $150 billion in CRF funds, the CARES Act set aside $11 billion specifically for the District of Columbia, U.S. Territories, and tribal governments, and the remaining 93% (or $139 billion) was allocated to the 50 states based on population size, using the most recent Census data available. While allocating aid based on population is a simple distribution formula to use, one shortfall is that it does not take “need” into consideration.

Any amount distributed to local government units was subtracted from the state government’s allocation. All general-purpose local governments with a population exceeding 500,000 were eligible, but were required to submit certification to the Treasury before April 17, 2020. Of the 171 eligible governments, 154 counties and cities were awarded funds.2 The number of local governments directly receiving CRF funds is a small fraction of the roughly 38,779 general-purpose governments in the United States.3 Figure 1 shows CRF allocations for the 50 states, with the portion allocated to the state in blue and the total amount allocated to counties and cities within the state represented by an orange dot, with the dot size varying by the total amount of money set aside for local governments.

Figure 1: Allocation of Federal Coronavirus Relief Funds

part 2

Source: “Payments to States and Eligible Units of Local Government.” U.S. Department of the Treasury. https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/136/Payments-to-States-and-Units-of-Local-Government.pdf

Of the $139 billion set aside for states and local governments, $111.4 billion is dedicated to states and the remaining $27.6 billion is allocated to local governments. The minimum state allocation is $1.25 billion, less any funds allocated to local governments. California received the largest share of CRF funds, comprising 11% of all state and local funding, followed by Texas (8%), Florida (6%), and New York (5%) respectively. Illinois received a total allocation of $4.9 billion, with $3.5 billion going to the state and $1.4 billion going directly to five counties and the City of Chicago. Sixteen states—Alaska, Arkansas, Connecticut, Idaho, Iowa, Louisiana, Maine, Mississippi, Montana, New Hampshire, North Dakota, Rhode Island, South Dakota, Vermont, West Virginia, and Wyoming—received funds only at the state level. State governments, however, can dedicate some or all of their CRF funds to local governments, and were initially encouraged to do so, though Treasury guidance includes no formal requirement or instruction.4

What’s Been Spent So Far?

The CARES Act specified that CRF monies could only be used for “necessary expenditures incurred due to the public health emergency with respect to” COVID-19.5 But what exactly constitutes an acceptable expenditure is not detailed in the legislation. The Treasury Department explained “acceptable expenses” in guidance and frequently asked questions (FAQ) documents. The Treasury’s most recent FAQ indicates that there is a wide range of activities that governments can use CRF funds for, and examples include: payroll for public health employees, mortgage/rent relief to households facing eviction or foreclosure, grants to small businesses, and transfers to local governments. Some allowable CRF expenses can also be paid for with funding available from other aspects of the CARES Act and related COVID-relief legislation, such as the $175 billion set aside for hospital and healthcare workers. With many new and increased expenses tied to COVID, states are tasked with determining which ones are most appropriate and efficient to use CRF funds for. The existence of overlapping pools of federal funds means states must strategize spending to get the maximum possible benefit from each program.

An August report from the Department of the Treasury Office of Inspector General showed that state governments had spent 24.5% of CRF funds between March 1 and June 30, with spending varying widely among the states—California, for example, reported that it had spent 100% of its state CRF funds, while South Carolina had spent 0%.6 As Congressional leaders and the White House debated the need for another round of stimulus, the small amount of aggregate spending reported gave a false impression that states did not have plans to spend the funds and that there was a lack of need for fiscal support from the federal government. For example, that same month the report was released President Trump signed an executive memorandum providing $300 in weekly supplemental unemployment payments from the federal government if states contribute an additional $100, and suggested that states use leftover CRF monies to pay their share. Echoing President Trump, Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin argued that states had “plenty of money” available to contribute to such a program. However, state governors noted that while some CRF money was unspent, much of it was already appropriated to other programs.7 Importantly, the Treasury report captures only “costs incurred” between March 1 and June 30,8 and it does not track how states plan to use CRF funds or states total COVID related expenses. States do not have to submit how they plan to spend CRF funds to the federal government, and only report incurred expenses on a quarterly basis. In addition, because some spending could be covered by CRF funding and/or other federal programs, states are devoting time to determine the best way to account for COVID related expenses, and are therefore incurring costs or encumbrances before allocating CRF funds to them.

How Do States Plan to Use CRF Money?

There is a lack of comprehensive information regarding how states plan to use CRF money at the national level, and even at the state level it can be difficult to discern the most updated plan for the funds.9 In some instances, the state legislatures have approved appropriations that allocate all available CRF funds to specific budget line-items, while in other states the plans have been less detailed and Governors have issued only general statements about their plans. We examine Illinois’ plan and compare it to plans in neighboring Indiana and Wisconsin, as well as California. California is included because it is the only state that reported spending all of its CRF funds by June. We group planned spending for each state into five broad categories:

- Grants for Economic Support refers to funds intended for businesses, nonprofit organizations, or residents to offset financial hardship;

- Internal Expenses refers to funds used to pay state and departmental costs, such as expenses associated with payroll or procurement;

- Healthcare refers to funds intended for programs and services tied specifically to treating and mitigating the spread of COVID-19 and other healthcare costs, including contact tracing, COVID testing, procurement of equipment like ventilators, and payments to long-term care facilities.

- Transfer to Other Governments refers to funds that are transferred from the state to counties, municipalities, school districts, public health departments, and other units of government for expenditures allowed under the CARES Act and/or purposes restricted by the state;

- Allocated for Undisclosed Purpose refers to funds for which spending has been discussed in the public record, but no line item or further description of their use has been offered;

- Unallocated refers to the leftover portion of a state’s CRF allocation, to which no legislative appropriation, executive order, or public statement refers.

Figure 2 compares spending plans for California, Illinois, Indiana, and Wisconsin.10 As Figure 2 shows, while California and Illinois have publicly available plans that detail how all CRF monies will be spent, Indiana and Wisconsin have unallocated portions. As discussed below, there are several reasons why funds may be unallocated, and none of the reasons indicate that the fiscal support is not needed.

Figure 2: Plans for CRF Monies for Selected States

part 3

Sources: “Overview of California Spending Plan.” (October 5, 2020). Legislative Analyst’s Office. https://lao.ca.gov/Publications/Report/4263#Major_Features_of_the_2020.201121_Spending_Plan; Illinois Public Act 101-0637. https://www.ilga.gov/legislation/publicacts/101/PDF/101-0637.pdf; “Gov. Holcomb Announces Nearly $44 Million to Aid Economic Recovery Effort.” (2020, May 29).; “Gov. Holcomb Launches $50 Million Initiative to Help Hoosiers Economically Recover.” (2020, June 5).; “Governor Announces $61 Million Education Relief Fund for Remote Learning.” (2020, June 22).; “Governor Announces $25 Million in Relief for Renters.” (2020, June 24).; “Gov. Holcomb Announces $61M for Education Connectivity, Devices and Resources.” (2020, August 19). https://calendar.in.gov/site/gov/event; Erdody, L. (2020, May 1). “State allocates $300M to local governments for coronavirus aid,” Indiana Business Journal. https://www.ibj.com/articles/state-allocating-300m-to-local-governments-for-coronavirus-aid; Erdody, L. (2020, October 20). “Indiana starting to spend down CARES Act money,” Indiana Business Journal. https://www.ibj.com/articles/state-starts-to-spend-down-cares-act-money; “Gov. Evers Provides Update on Investments made in Public Health, Emergency Response, and Economic Stabilization.” https://content.govdelivery.com/accounts/WIGOV/bulletins/2a6cc7c

* Illinois appropriations sum to $3.70 billion, which is higher than the state’s federal allocation of $3.52 billion.

The four states in this analysis illustrate remarkably different approaches to communicating plans for CRF funds. In Illinois, all funds were legislatively appropriated as part of Public Act 101-0637, which was signed into law on June 10, 2020. While that law serves as the state’s FY2021 appropriations bill, the sections regarding CRF funds amends the FY2020 budget, making Illinois’ CRF funds supplemental appropriations to the FY2020 budget.

Detailing Illinois’ Plans and Flow of Funds

Illinois lawmakers appropriated 41.36% for internal expenses, 28.67% for grants for economic support, 23.22% for healthcare, and 6.75% for transfers to local governments. California appropriated all of its CRF funds as part of the current year budget (FY2021) on June 26, 2020, opting to transfer 65.96% to local governments for specified uses, retain 28.27% for internal expenses, and allocate 5.77% to grants for economic support. The $2.693 billion (28.27%) appropriated for internal expenses is to offset state costs in areas such as public safety, public health, and the CalWORKs program.11 A large portion of the $6.283 billion transferred to local governments is earmarked to provide support to students, businesses, nonprofits, and residents, but is administered by local units of government rather than the state. The funds have already been transferred to these local governments, with $4.5 billion going to local education agencies for learning loss mitigation, $1.289 billion to counties for public and behavioral health programs, and $500 million to cities for homelessness and public safety.

Detailing Illinois’ Plans and Flow of Funds

We examined the flow of CRF money through the state of Illinois in detail. The five largest counties in the state and the City of Chicago received funds directly from the federal government, totalling $1.4 billion. The State of Illinois received $3.5 billion in CRF monies, and created the Coronavirus Urgent Remediation Fund and the Local CURE Fund to accept and disperse these funds. The new funds allocate money to 17 different programs, managed or administered by six state agencies. Figure 3 summarizes the flow of CRF funds in Illinois from the federal government to ultimate planned spending.

The largest portion of Illinois CRF funds, $1.5 billion, is appropriated to the Illinois Emergency Management Agency to reimburse state agencies for any costs eligible for payment from federal CRF monies. The Illinois Housing Development Authority is appropriated $396 million to administer affordable housing grants, emergency rental assistance, and emergency mortgage assistance. The Illinois Department of Human Services is appropriated $62 million for mental health and substance abuse programs and Illinois Welcoming Centers. The Illinois Criminal Justice Authority is appropriated $20 million for the Coronavirus Emergency Supplemental Funding (CESF) Program, a federal program intended to address the personnel, equipment, and health needs of jails, prisons, and correctional facilities. The Department of Healthcare and Family Services is appropriated $830 million for grants to medical providers. In addition to the Coronavirus Business Interruption Program and a program to provide technical assistance to underserved populations, the Department of Commerce and Economic Opportunity oversees the Local CURE Program. Local CURE plans to distribute a total of $250 million to Illinois local governments based on population, excluding the City of Chicago, Cook County, DuPage County, Kane County, Lake County, and Will County, which received funds directly from the federal government.

Figure 3: Flow of CRF Funds in Illinois

part

Note: This chart shows the state’s plan for spending, and does not necessarily represent actual expenditures.

Source: “Payments to States and Eligible Units of Local Government.” U.S. Department of the Treasury. https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/136/Payments-to-States-and-Units-of-Local-Government.pdf; Illinois Public Act 101-0637.

In contrast, planning for CRF spending in Indiana and Wisconsin has been more fluid. The State of Wisconsin allocated $1.8 billion of its $2 billion CRF monies in September 2020,12 and Governor Tony Evers announced uses for the other $200 million in a series of press releases throughout October 2020.13 However, Governor Evers’ October 20, 2020 press release amended the September allocation and provided an updated table of Wisconsin’s current plan. According to that most recent statement, Wisconsin is budgeting the largest portion (60.77%) for healthcare costs, 22.20% of funds are slated to be used for economic support grants, and 10.06% will be transferred to local governments. The State of Indiana has not offered any kind of comprehensive plan for its CRF funds, although statements on spending plans have been made by Indiana Governor Eric Holcomb and in testimony from Indiana Office of Management and Budget Director Cris Johnston.14 This collection of announcements sums to $1.7 billion in planned spending, leaving $742 million unallocated, or 30.39% of Indiana’s CRF funds. Johnston said in August 2020 that the state was waiting on guidance from the federal government before allocating funds.15

These two different approaches to planning for CRF funds illustrate states’ competing interests of transparency, spending plans before the December deadline, and leaving enough flexibility to respond to changing needs or changing federal guidance. Stakeholders have a better understanding of the comprehensive plans for Illinois and California, including how much money is allocated to specific uses and programs. In the case of California, early appropriations seem to have contributed to the state’s ability to report spending all of its funds faster than in other states. While the plans in Wisconsin and Indiana are harder to analyze and less formalized, they leave latitude to respond to changing conditions and Treasury guidelines.

Why Does it Appear States are Slow to Spend?

There are several reasons why states may be slow to spend or even plan for spending CRF funds. First, as previously noted, the Treasury Department is collecting information from state governments only on a quarterly basis. States also need to determine all the federal programs COVID-related expenses are eligible for (including CRF funds), and because of this, there may be a lag between when an expenditure occurs and when a state encumbers the use of CRF funds on the pertinent line-item. Therefore, the Treasury reports do not capture states’ total COVID-related spending.

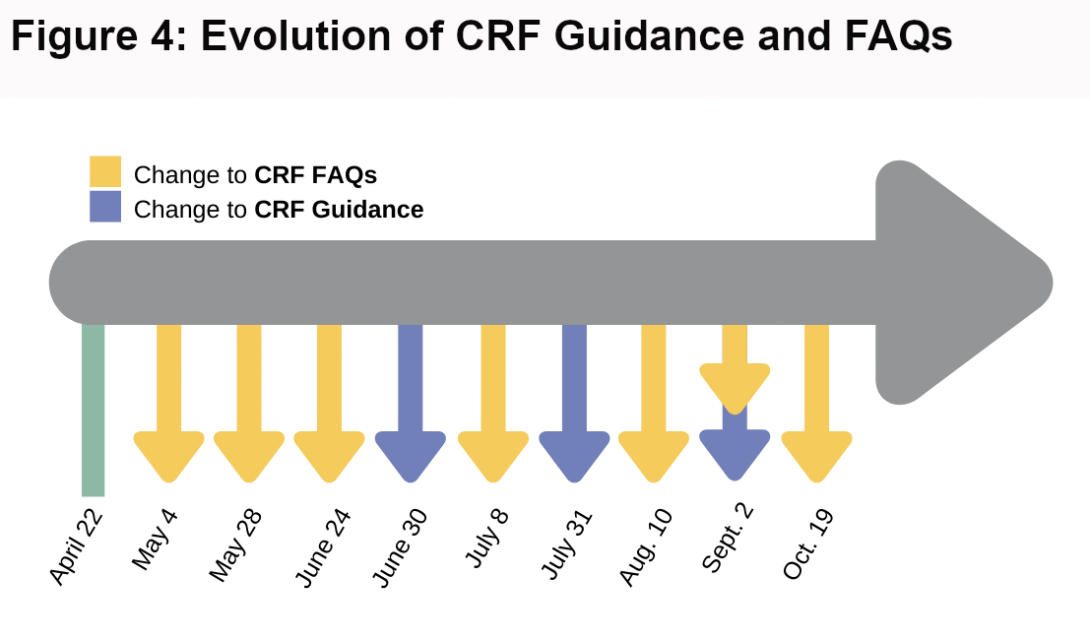

Another reason is that what exactly constitutes a necessary expense tied specifically to COVID-19 is not defined in the CARES Act. The Treasury Department has produced guidelines and Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) for governments eligible to use CRF funding, and these documents have changed. As Figure 4 shows, the Treasury Department updated its guidance and FAQ numerous times after publishing the first versions on April 22. In a survey of state and local governments, the Government Finance Officers Association found that the majority of respondents (51%) indicated that the Treasury’s guidance was unclear and found the documents “incomplete and conflicting.”16 This in-turn has delayed the use of CRF funds. As previously mentioned, Indiana, for example, did not appropriate the bulk of its CRF funds until October 2020 when it received feedback from the Treasury Department on its plans. Based on changing needs and evolving Treasury guidance, Wisconsin Governor Tony Evers revised the state’s original spending plans. State governments may be reluctant to spend down their CRF funds quickly in order to preserve some flexibility to respond to both changing needs within their states and further changes in guidelines from the Treasury.

part4

Another reason for delays in spending down CRF funds is that states may be taking cautious approaches out of concern for future federal audits and fear that some projects may be determined not to be an acceptable expense. In such a scenario the state would have to absorb the cost, which would compound the fiscal challenges state governments are already grappling with due to revenue shortfalls. States with pre-COVID fiscal challenges may be taking an especially conservative approach because they may be least able to absorb such costs. In documenting that expenses are COVID-related, the uncertainties previously mentioned pose a challenge as to whether state agencies should spend time and effort creating new accounting systems or proceed under the assumption that tracking such spending is a one-time effort.

Regardless of the approach taken, states have to carefully track how CRF monies are spent, both internally and by third-parties, like grant recipients and local governments, and this may also be causing spending delays. Illinois set aside $250 million for local governments, but local governments have to apply to the Illinois Department of Commerce and Economic Opportunity to access that funding. Moreover, the state reimburses local governments for expenditures. Because of this, local governments have to submit expenses to the state for reimbursement, and the state reviews the expenditure before dispensing CRF money. In contrast, California has already transferred funds to local governments in full—$4.5 billion to local education agencies, $1.3 billion to counties, and $500 million to cities—but is requiring localities spend the funds on uses outlined by the state. Rather than reimbursing expenditures as they happen, the state broadly dictated how the funds are to be spent and is requiring reporting after the fact. For example, the state distributed $4.5 billion of its $9.5 billion in CRF funds to 2,263 local education agencies (LEAs) in full on August 21, 2020 specifically to combat learning loss mitigation.17 The $4.5 billion was disbursed to 2,263 local education agencies (LEAs) in full on August 21, 2020. The transmittal letter directs LEAs in how the funds should be used. The state determined eligibility and allocation amount based on a set of criteria.18 LEAs were notified of eligibility and had to submit an application of assurance by August 5, 2020.

Last, a final issue is that creating new programs and augment existing ones is a time consuming process, especially considering that demand for many government programs has increased dramatically. The State of Alabama intended to use some of its CRF monies for a new program to bolster online learning for students. But when state officials realized that the funds needed to be spent by December, they dropped the plan, saying that there was no way they could get the program up and running fast enough.19 According to the August Treasury report, the State of Alabama had spent just 0.1% of its funds. Even when states direct funds toward existing programs, it can be challenging to increase capacity. States have struggled to address the spike in unemployment claims as their uninsurance programs were designed and staffed to serve much lower numbers of people than are now requesting assistance.20 In other instances, the capacity of existing facilities and programs, like childcare and homeless shelters, has had to be reduced to comply with social distancing protocols implemented to help curb the spread of COVID-19. For example, despite receiving $8.9 million in CRF funds from the State of Utah, the state’s homeless service providers are struggling to meet the surge in demand for shelters. The number of people experiencing homelessness has sharply risen, but shelter use is below the previous year as shelters have had to decrease capacity of existing facilities in an effort to mitigate the spread of COVID-19. Because of the need for social distancing, shelters have consistently been at capacity and are turning people away. One domestic violence shelter reported turning away 300 people due to reduced capacity. Providers are now working to set up overflow facilities and create partnerships for hotel and motel vouchers.21

Conclusion

The scale of the fiscal impact on state and local finances is significant. Between 2020 and 2022, state and local governments’ are projected to experience revenue shortfalls totaling nearly $500 billion according to one estimate. In addition to that estimated revenue loss, governments are faced with increased costs and spending needs tied to COVID-19. Given an array of needs, states are tasked with planning how to spend CRF funds in the most strategic way possible. Determining the best use of CRF funds is challenging in an environment in which Treasury guidance continues to evolve, public health forecasts on how long the pandemic itself will last vary, and the prospect of Congress passing another stimulus bill is uncertain. Compounding all of that uncertainty, there are many stakeholders (elected officials, department heads, local governments, non-profits, businesses, and residents) with competing needs and ideas as to how to spend the CRF funds. The ongoing nature of the pandemic with second and third waves of spiking case loads will strain state and local finances even more. With the prospect of more direct support to state and local governments in the near term uncertain, Congress should at a minimum extend the deadline for CRF spending beyond December 30 to allow governments to maximize how those funds are used.

Click Here To View The PDF Of This Report

_______________________________________________

1CARES Act, 116-136 U.S.C VI § 601

2“Eligible Units of Local Government,” U.S. Department of the Treasury. https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/136/Eligible-Units.pdf

3McQuillan, S. (2020, August 21). States Still Struggling to Use Federal Covid Relief Funds. Bloomberg Tax. https://news.bloombergtax.com/daily-tax-report-state/states-still-struggling-to-use-federal-covid-relief-funds

4CARES Act, 116-136 U.S.C V § 601.

5This does not include spending by local governments that received funds directly from the federal government.

6Werner, E. et al. (2020, August 10). “Nation’s governors raise concerns about implementing Trump executive moves, call on Congress to act.” The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/us-policy/2020/08/10/trump-coronavirus-stimulus-congress/

7Delmar, R. (2020, July 2). Coronavirus Relief Fund Reporting and Record Retention Requirements [Memorandum]. Department of the Treasury Office of the Inspector General. https://www.treasury.gov/about/organizational-structure/ig/Audit%20Reports%20and%20Testimonies/OIG-CA-20-021.pdf

8The National Conference of State Legislatures and the National Association of Counties each have online trackers that are updated daily, but the data is not always comprehensive.

9Sources: “State of California 2020-21 Budget Summary.” p. 21. http://www.ebudget.ca.gov/2020-21/pdf/Revised/BudgetSummary/FullBudgetSummary.pdf; Illinois Public Act 101-0637. https://www.ilga.gov/legislation/publicacts/101/PDF/101-0637.pdf; “Gov. Holcomb Announces Nearly $44 Million to Aid Economic Recovery Effort.” (2020, May 29).; “Gov. Holcomb Launches $50 Million Initiative to Help Hoosiers Economically Recover.” (2020, June 5).; “Governor Announces $61 Million Education Relief Fund for Remote Learning.” (2020, June 22).; “Governor Announces $25 Million in Relief for Renters.” (2020, June 24).; “Gov. Holcomb Announces $61M for Education Connectivity, Devices and Resources.” (2020, August 19). https://calendar.in.gov/site/gov/event; Erdody, L. (2020, May 1). “State allocates $300M to local governments for coronavirus aid,” Indiana Business Journal. https://www.ibj.com/articles/state-allocating-300m-to-local-governments-for-coronavirus-aid; Erdody, L. (2020, October 20). “Indiana starting to spend down CARES Act money,” Indiana Business Journal. https://www.ibj.com/articles/state-starts-to-spend-down-cares-act-money; “Gov. Evers Provides Update on Investments made in Public Health, Emergency Response, and Economic Stabilization.” https://content.govdelivery.com/accounts/WIGOV/bulletins/2a6cc7c

10Coronavirus Relief Fund Monies Under the Federal CARES Act. (2020, September 9). Wisconsin Legislative Fiscal Bureau. p. 3. https://docs.legis.wisconsin.gov/misc/lfb/misc/123_coronavirus_relief_fund_monies_under_the_federal_cares_act_9_9_20.pdf

11Gov. Evers Announces nearly $50 million in COVID-19 Support for Wisconsinites. (October 5, 2020). https://content.govdelivery.com/accounts/WIGOV/bulletins/2a44989; Gov. Evers Invests Additional $100 Million in Wisconsin Small Businesses and Economic Stabilization. (2020, October 6). https://content.govdelivery.com/accounts/WIGOV/bulletins/2a4759f; Gov. Evers, DCF Secretary Amundson Announce $50 Million for Additional Child Care Counts Payments for Early Care and Education. (2020, October 13). https://content.govdelivery.com/accounts/WIGOV/bulletins/2a57c73

12Beginning in May and extending through August, Indiana Governor Holcomb announced $179.7 million worth of programs funded with CRF monies through a series of press releases. On May 1, 2020, he verbally announced that $300 million would be transferred to Indiana local governments. Based on recent testimony from Indiana Office of Management and Budget Director Cris Johnston, the State has allocated another $434 million to specific uses, estimated it would spend $500 million on eligible payroll expenses, and has unspecified plans for $224.7 million. Press releases accessed at https://calendar.in.gov/site/gov/event; Erdody, L. (2020, May 1). “State allocates $300M to local governments for coronavirus aid,” Indiana Business Journal. https://www.ibj.com/articles/state-allocating-300m-to-local-governments-for-coronavirus-aid; Erdody, L. (2020, October 20). “Indiana starting to spend down CARES Act money,” Indiana Business Journal. https://www.ibj.com/articles/state-starts-to-spend-down-cares-act-money

13Smith, B. (2020, August 4). “Indiana Still Hasn’t Spent Most Of Its Federal CARES Act Money.” Indiana National Public Radio. https://indianapublicradio.org/news/2020/08/indiana-still-hasnt-spent-most-of-its-federal-cares-act-money/

14Haroon, M. (2020, October). “CARES Act Coronavirus Relief Fund.” Government Finance Officers Association. https://gfoaorg.cdn.prismic.io/gfoaorg/e59192d8-9f81-47ea-8134-29e4c5869b66_CRF+Report_Final-10-20.pdf p. 6

15Funding Results, Learning Loss Mitigation Fund. State of California. https://www.cde.ca.gov/fg/fo/r14/llmf20result.asp

16Funding Methodology, Learning Loss Mitigation Fund. State of California. https://www.cde.ca.gov/fg/cr/learningloss.asp

17McQuillan, S. (2020, August 21). States Still Struggling to Use Federal Covid Relief Funds. Bloomberg Tax. https://news.bloombergtax.com/daily-tax-report-state/states-still-struggling-to-use-federal-covid-relief-funds

18Hsu, T. (2020, April 3). “Coronavirus Layoff Surge Overwhelms Unemployment Offices.” The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/19/business/coronavirus-unemployment-states

19McQuillan, S. (2020, August 21). States Still Struggling to Use Federal Covid Relief Funds. Bloomberg Tax. https://news.bloombergtax.com/daily-tax-report-state/states-still-struggling-to-use-federal-covid-relief-funds

20Auerbach, A. et. al. (2020, September 24). Fiscal Effects of COVID-19. Conference draft. Brookings. https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/Auerbach-et-al-conference-draft.pdf

21 Stevens, T. (2020, September 21). “Homeless service providers throughout Utah see spikes in people seeking help as the pandemic wears on.” The Salt Lake Tribune. https://www.sltrib.com/news/2020/09/20/homeless-service/