How States Prepared for the Storm – and a Warning for the Future

Introduction

blog

April 19, 2021

By William Glasgall, Senior vice president and director of state and local initiatives at the Volcker Alliance

As the COVID-19 pandemic spread across the US and the economy shut down in early 2020, warning sirens blared in statehouses from Hawaii to Maine. Hundreds of billions of dollars in budgeted revenues looked set to vanish, leaving officials to reckon with painful decisions to keep their states’ books in balance.

An unprecedented $5 trillion in federal pandemic aid to individuals, businesses, and state and local governments, equivalent to more than a fifth of the nation’s gross domestic product, along with a nationwide vaccination campaign, have helped keep COVID-19 at bay and state revenues from collapsing.

Indeed, total state tax revenue in the twelve months ending in February fell only 0.2 percent from the previous year, according to Lucy Dadayan, senior research associate at the Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center in Washington. But states also found that even without the aid bills enacted by Congress in 2020-21, many were in better financial condition than they originally feared. The Volcker Alliance’s latest annual report on states, Truth and Integrity in State Budgeting: Preparing for the Storm, explains why this was so.

Based on primary research conducted at eight US universities, including the Department of Public Administration, College of Urban Planning and Public Affairs at University of Illinois at Chicago,, the study covered fiscal 2015 through 2019 and features fifty individual state report cards and an online data lab.

The report found that during the record-long economic recovery that came to an end in 2020, many states used the benefits of improving employment and revenues to bolster the sustainability of their budgetary practices. On average, states showed steady increases in the annual grades produced by the Volcker Alliance in five fundamental categories: budget forecasting, budget maneuvers, reserve funds, legacy costs, and transparency.

blog2

Many of these improvements resulted from statutory changes and should prove durable over the long haul and are likely to help support their current recovery and their longer-term fiscal health.

Let’s drill down into the five budgetary categories and then highlight some areas and states that prepared well or still have a lot of work ahead of them:

Budget forecasting. The Alliance advocates for states adopting binding consensus revenue estimates and making predictions about revenues and expenditures for more than the next fiscal year. The average grade in the category was C, with marks restrained by a lack of estimates prepared jointly by governors and legislators, as well as by an absence of long-term revenues or expenditure estimates in many states. Only ten states won As. Three – Alabama, Missouri, and North Dakota – posted D-minus marks, the lowest possible.

Budget maneuvers. The Alliance suggests that states should pay for expenditures with recurring revenues earned the same year. Yet many states use one-time actions, such as moving budgeted costs to the future, bringing expected revenues into the current year, or using proceeds from sales of bonds or assets to achieve budgetary balance. The category average was B, with the use of such one-time actions decreasing slightly nationwide amid the economic recovery. Indeed, seventeen states achieved top A averages by largely avoiding the use of one-time tactics, and just one state, Pennsylvania, was given a D-minus for the study period.

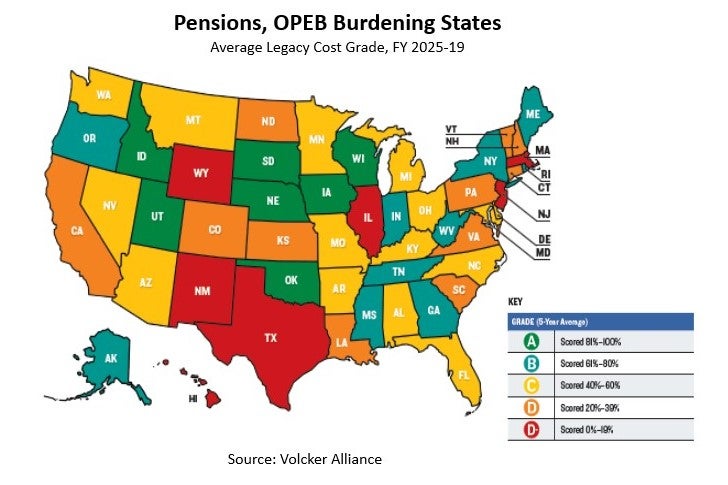

Legacy costs. The Alliance recommends that states consistently make actuarially recommended contributions for public employee pension and other postretirement benefits (OPEB), principally health care. Those failing to make such contributions may see increasing pressure on future budgets if the costs of supporting long-term liabilities crowd out spending for essential services. Of all the categories studied, this one was the most challenging for states (see map). Seven states (Idaho, Iowa, Nebraska, Oklahoma, South Dakota, Utah, and Wisconsin) scored A averages. But seven others (Hawaii, Illinois, Massachusetts, New Jersey, New Mexico, Texas, and Wyoming, the last two especially notable for their abundant fiscal reserves), were given D-minuses. The average mark for all states was only a C, with thirty-three states at that level or below.

Reserve funds. The Alliance advocates for states enacting clear policies for rainy day fund deposits and withdrawals and adjusting fund levels for the historical volatility of their revenues. With flush revenues allowing many states to set aside record-high rainy day fund balances, the average grade for fiscal 2015-19 was a respectable B.

Transparency. The Alliance believes that states should provide the data that public officials and citizens need to understand budgets. This includes online disclosure of budgetary information; public reporting of the scope and cost of tax expenditures, such as exemptions, credits, and abatements; and reporting of the cost of deferred infrastructure maintenance. A lack of information on deferred infrastructure costs held down states’ overall performance, with only three—Alaska, California, and Tennessee—averaging A marks. Arkansas, which was penalized for its lack of comprehensive online budgetary disclosure, was the lowest-graded state, with a D average.

Overall, the Alliance’s latest crop of budget grades provides a useful guide to states’ ability to weather downturns. While COVID-19 brought about such a severe disruption in the nation’s economy that the White House, Federal Reserve, and Congress and had little choice but to intervene, states such as New York, which is counting on massive federal aid, recovering GDP, and new taxes on millionaires to finance a spending increase of about 11 percent for fiscal 2022, may be in for an unpleasant surprise as Washington’s largesse winds down.

Across the US, state policymakers should take the time now to review their pre-pandemic achievements—and shortcomings—to help set sustainable budget policies as the nation returns to normal.

The Volcker Alliance is a nonpartisan, nonprofit 501(c)3 organization in New York. Reporting for this article was also contributed by Alliance associate director Noah Winn-Ritzenberg and by Katherine Barrett and Richard Greene, Alliance special project consultants and senior advisers to the Government Finance Research Center.