Do states with graduated structures change tax rates more frequently than states with a flat structure?

blog

Jan 21, 2020

By David Merriman and Amanda Kass

Merriman is Stukel Presidential Professor Dept. of Public Administration at the University of Illinois at Chicago, leader of the Institute of Government & Public Affair’s (IGPA) Working Group on the Fiscal Health of Illinois, and a member of the GFRC faculty advisory board. Kass is associate director of the GFRC.

Illinois voters will face an important question on the 2020 ballot: whether to amend the Constitution to permit a graduated income tax structure that allows the tax rate to rise as income increases. Currently, Illinois only permits a flat rate tax that applies a single rate to all taxable income.

Some have argued that permitting a graduated structure will open the door for frequent tax hikes. Central to this argument is a belief that the complexity of graduated structures makes it easier to gain political consensus for tax policy change since such changes need not apply to all taxpayers. We collected and analyzed data on historical tax policies in states with flat and graduated rate structures to compare the frequency of tax policy change. (For analysis of the revenue implications under various graduated rate structures see this Institute of Government and Public Affairs report). This blog discusses research challenges and highlights some preliminary findings:

Comparing income tax policy changes between states with different structures is difficult for a variety of reasons.

- Readily available data are messy and sometimes inaccurate. The Tax Foundation data we use for this preliminary analysis is the best available comprehensive compilation, but we have found, and are checking, inconsistencies and inaccuracies in a few cases.

- Not all tax changes are due to lawmakers’ explicit actions. Many states’ tax systems are synchronized with portions of the federal income tax system. Because of this, changes in federal income taxes can trigger changes in state taxes. Changes may also occur because state tax provisions automatically change each year. For example, nearly half of the states with graduated structures automatically adjust income tax brackets with inflation annually.

- There are many different parts of tax policy. Tax liabilities may depend on tax deductions, credits and other components as well as tax rates. Our analyses focus primarily on legislated changes in tax rates for single-filers, and does not necessarily reflect a complete picture of changes in tax liabilities.

So, do states with graduated structures change tax rates more frequently than states with a flat structure?

blog

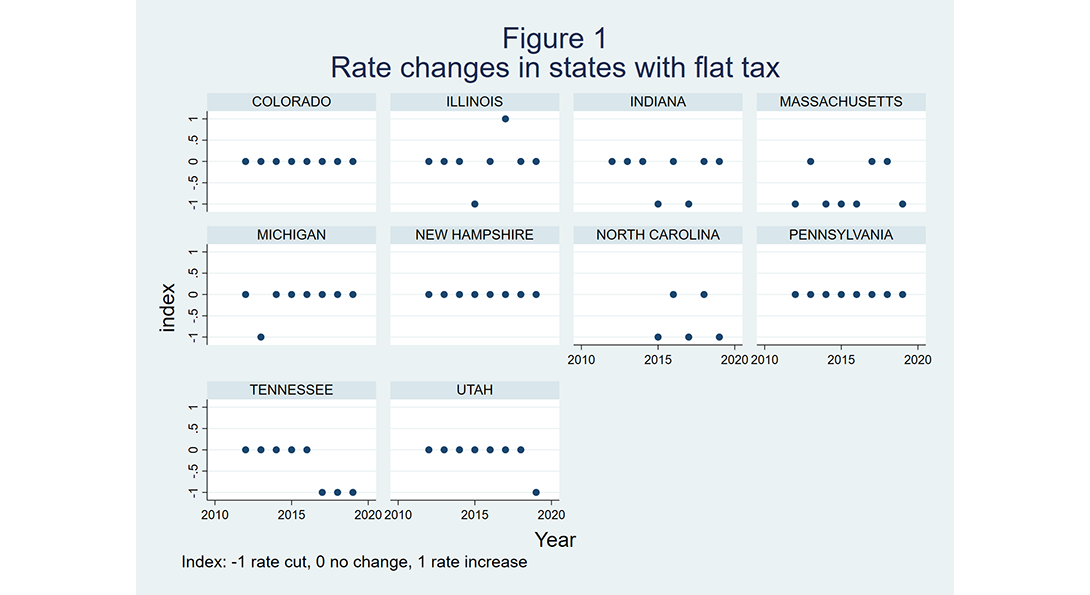

Consider first the ten states with flat rate income taxes. Figure 1 shows that three of these states (CO, NH and PA) made no rate changes during the 2011 to 2019 period. The other states enacted at least one tax rate cut during this relatively prosperous period, with Massachusetts making five very small cuts while North Carolina and Tennessee cut their rates three times. Only Illinois raised its tax rate during this period.

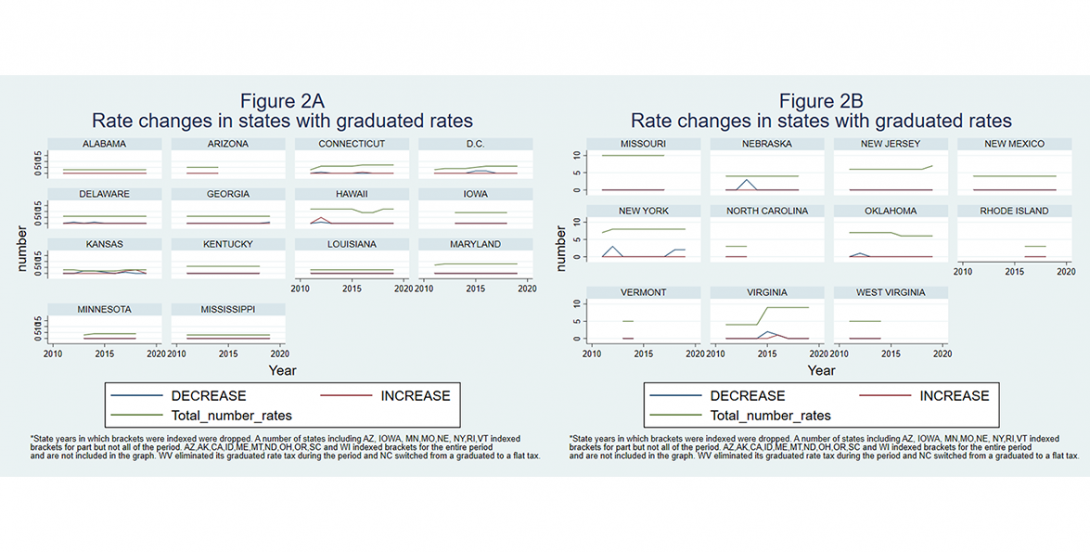

Figures 2A and 2B show information about the total number of brackets and tax rate changes for 24 states and the District of Columbia that have graduated structures. We show three lines for each state in these figures. The top (green) line shows the total number of tax rates per state each year. For example, Alabama had three rates each year during the period, while the number of rates in Connecticut increased from three in 2011 to 7 in 2019. A second (red) line shows the number of rates that were increased each year. Hawaii, for example, increased five of its 12 rates in 2012. A third (blue) line shows the number of rates that were decreased each year. New York decreased three of its rates in 2012.

Blog

In the ten flat rate states there were 77 opportunities for tax changes in the period we studied. In 60 cases (77.9%) the state did not change rates. In 16 cases (20.8%) the state cut rates, and in one case (1.3%) a state increased the rate.

Rate changes were less common in states with graduated structures. Because these states had multiple rates in each year, they had many more opportunities to alter rates but rarely did so. Counting all of the rates in each of the states in each of the years we studied, the states had 1,036 opportunities for rates changes. In 995 cases (96%) the states did not change the rate. In only 12 of these cases (1.2%) states raised the tax rate and in only 29 cases (2.8%) states cut tax rates.

Overall, with data over a relatively short (and prosperous) period the empirical evidence provides little systematic support for the hypothesis that states with graduated structures are significantly more likely to make rate changes when compared to states with flat rate systems. That said, we do not believe these preliminary results are definitive. The most relevant question is whether a state which changes from a flat to a graduated rate system might be more or less likely to alter its rates in the future. To provide a more definitive answers to this question we would need to control for underlying characteristics of states’ economic and political systems as well as their choice of tax structure. Furthermore, in future research we wish to study tax changes during various stages of the business cycle, as well as further refining and cleaning our data.