Following the Money: Notes on the State and Local Fiscal Recovery Fund

start Heading link

April 6, 2022

By Amanda Kass and Philip Rocco

This is the first in a series of posts supported by the Joyce Foundation describing the work for our project tracking how the American Rescue Plan Act is affecting city governments’ investments in Community Violence Interventions (CVIs). In it, we describe how state and local recipients of the American Rescue Plan Act’s State and Local Fiscal Recovery Fund dollars may allocate their funding and the tools available for tracking these funds. We also discuss some challenges and pitfalls of interpreting data on how these units of government are using ARPA dollars.

***

The passage of the American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) and creation of the Coronavirus State and Local Fiscal Relief Fund program is nothing short of a milestone in the history of American fiscal federalism. Simply put, in passing this law, Congress made the largest one-time transfer of multipurpose federal funds to state and local governments in half a century. The $350 billion Coronavirus State and Local Fiscal Recovery Fund (SLFRF) program is nearly double the amount of multipurpose aid Congress provided to states, territories, tribal governments and local governments in the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic. For context, the SLFRF is nearly equivalent to what Congress delivered to state and local governments in unrestricted federal aid over the course of 15 years through the General Revenue Sharing program (the total amount of aid distributed between 1972 and 1986 is roughly $388 billion in current dollars). The SLFRF program also provides aid to a far greater number of local governments than its predecessor, the Coronavirus Relief Fund (created as part of the CARES Act). Only 154 counties and cities received Coronavirus Relief Fund aid whereas more than 40,000 local governments are eligible for SLFRF dollars.

What makes the SLFRF noteworthy is not just its size but the variety of purposes to which it allows state and local governments to devote resources, which range from replacing revenue lost as a result of the pandemic to lead pipe remediation. The program’s flexibility is intentional. Between 2020 and 2021, state and local officials educated members of Congress as well as the Treasury Department staff on their pandemic-related fiscal challenges and the difficulty of allocating funds under tight and ambiguous statutory constraints. And indeed, the SLFRF’s design seems to reflect lessons from the Coronavirus Relief Fund. Yet this flexibility, and the discretion given to recipient governments under the SLFRF program, can also make it challenging to track how federal funds are being spent.

In this post, we describe how state and local recipients of SLFRF dollars can allocate their funding and the resources available for tracking these funds. While there are national organizations, like the National League of Cities, building online dashboards to capture this information, we discuss some challenges and pitfalls of interpreting data on how governments are using ARPA dollars.

paragraph 1 Heading link

Using (and Tracking) SLFRF Dollars

What makes the SLFRF a distinctive opportunity––and what makes it difficult to track SLFRF dollars––is the flexibility it affords recipient governments. The text of the American Rescue Plan Act itself specified four, board statutory uses in which governments can allocate money. First, they can devote funds to responding to the public health and economic impacts of the ongoing pandemic. Second, they can use the money to fund government services and replace public sector revenue lost during the pandemic. Third, they can leverage federal funds to provide premium pay to essential workers. Finally, governments can commit SLFRF dollars to the implementation of water, sewer, and broadband infrastructure projects. Recipient governments have until the end of 2024 to decide how they’re going to use the money, and all the money must be expended by the end of 2026.

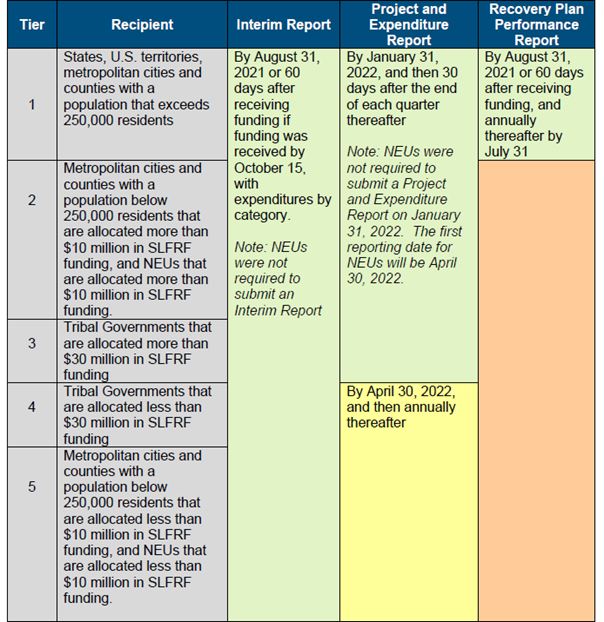

In implementing the SLFRF program, the U.S. Treasury Department issued rules and a guidance that provided additional flexibilities, and which contained more detailed information about how governments can use SLFRF dollars and how they have to report spending to the federal government. One consequence of this flexibility is “tiered” reporting requirements. Recipient governments are categorized into one of five tiers, and the reporting rules vary by tier (as captured in this chart). Under the Treasury regulations, smaller units of government (those in “Tier 5”) bear a smaller paperwork burden than larger ones. One additional complication in tracking the activities of smaller governments (those designated non-entitlement units or “NEUs”) is that the distribution of SLFRF dollars and tracking of that distribution is done by state governments. Once NEUs spend SLFRF dollars they have to submit project and expenditure reports to the Treasury Department.

Under the Treasury regulations, all governments have to account for how they spend SLFRF dollars using specific expenditure categories created by the Treasury Department. Starting April 2022 there are 83 specific categories.

paragraph 2 Heading link

For our research, we’re collecting data from the “Project and Expenditure Report” and the “Recovery Plan and Performance Report” (or “Recovery Plan”). While these two documents capture different information, both capture planned and actual spending at the project level. The project level is the most granular level of detail, and in its guidance the Treasury Department specifies that projects are “new or existing eligible government services or investments funded in whole or in part by SLFRF funding” (p. 19). Every project has to be assigned one of the expenditure categories. Importantly a project can only be assigned one expenditure category even if it could fall into multiple, and it is up to the recipient governments to assign an expenditure category to a project.

paragraph 3 Heading link

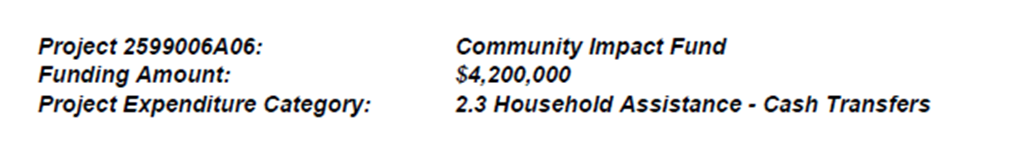

This screenshot is an example of a project from the City of Albuquerque’s 2021 Recovery Plan (p. 16):

paragraph 4 Heading link

For this project the City of Albuquerque is planning to use $4.2 million to provide a direct cash transfer of $1,000 per household to low-to-moderate income households negatively impacted by the pandemic, and this project has been assigned to expenditure category 2.3 (as shown in the screenshot).

Monitoring Challenges

While the reports governments have to submit to the Treasury Department provide lots of information, following the trail of SLFRF dollars is more complicated than it at first appears for several reasons. A first set of concerns relates to the reporting rules varying by type of jurisdiction, population size, and how much money a government receives. Governments in tiers 2-5, for example, do not have to submit Recovery Plans. While tiered reporting requirements might make administrative sense––especially given the constraints on staff capacity in smaller municipalities––it also means that we won’t have information about how all recipient governments are spending their money at the same time. For example, whereas large municipalities (with populations of over 250,000) will submit quarterly Project and Expenditure Reports, smaller municipalities will only submit these documents annually.

The Recovery Plans and Expenditure Reports are also only capturing information at one point in time, so information in them may be outdated by the time they are published and made available to the general public. For the Recovery Plans, the Treasury Department specified a minimum amount of information governments need to include, and there’s wide variation in the reports between governments. Chicago’s 2021 report is just 7 pages, for example, while Boston’s report is 143 page. Hence, while 2021 Interim Reports and Recovery Plans are currently available on the SLFRF website, here, we should be cautious about interpreting aggregate data from them as representative of what all recipient governments are doing with SLFRF dollars.

Another set of challenges has to do with the expenditure categories. One issue is that the Treasury Department has changed and added new codes. Whereas under the previous rules there were 67 categories, starting April 2022 there are now 83 categories. Because of these changes the expenditure categories used in the 2021 reports will be different from the ones used in subsequent reports. As an example, “Community Violence Intervention” projects were originally expenditure category 3.16, but starting April 2022 they will be coded as category 1.11, and category 1.11 was previously for “Substance Use Services” projects but going forward these projects will be category 1.13.

More importantly, while the Treasury has developed a series of readymade categories and subcategories into which recipients must classify ARPA-funded projects. Treasury’s data submission portal requires that all projects are classified with one and only one category. Because assigning a project to a category is left to recipient governments this means that for some types of projects recipients may code the same type project differently.. While this may be unproblematic for projects with an unambiguous purpose––such as COVID testing––for others it will create inconsistencies for projects with multiple purposes. For example, setting up mobile hygiene stations for unhoused persons could ostensibly fall under the public health, negative economic impact, or water infrastructure categories. The fungibility of revenue makes the revenue replacement category particularly tricky to track, a topic we’ll delve into deeper in a future post.

A final challenge is that different types of financial information are captured in different reports and sometimes even in the same report. The Recovery Plans, for example, contain two types of financial information: planned spending and actual expenditures. Planned spending is just that–what a government is planning to spend its money on. For example, as of 2021, Baton Rouge is planning to use one-third (or $56 million) of its SLFRF aid on stormwater infrastructure. In contrast to planned spending, expenditures capture spending that has already taken place. In the same report, Baton Rouge reported that it had spent just $3.39 million (or 6% of total planned spending) on stormwater infrastructure as of August 31, 2021. Governments can change their spending plans, so in tracking SLFRF spending over time it’s important to differentiate between planned spending and actual expenditures and track both over time.

These and other challenges confront researchers as they begin to follow how state and local governments use SLFRF dollars. And while they are hardly insurmountable, they suggest that a great degree of caution is warranted before interpreting aggregate spending data as evidence of what these governments are or are not doing. Especially given the delays and inconsistencies that have defined the reporting process, as well as the inherent ambiguity of some categories of spending. Because of such challenges data aggregation must be paired with careful qualitative analysis to ensure that we know not just where the money is going, but what it is doing, and what it means.

In a future post, we’ll describe a specific challenge that has emerged in our analysis of the use of SLFRF dollars on Community Violence Initiatives.